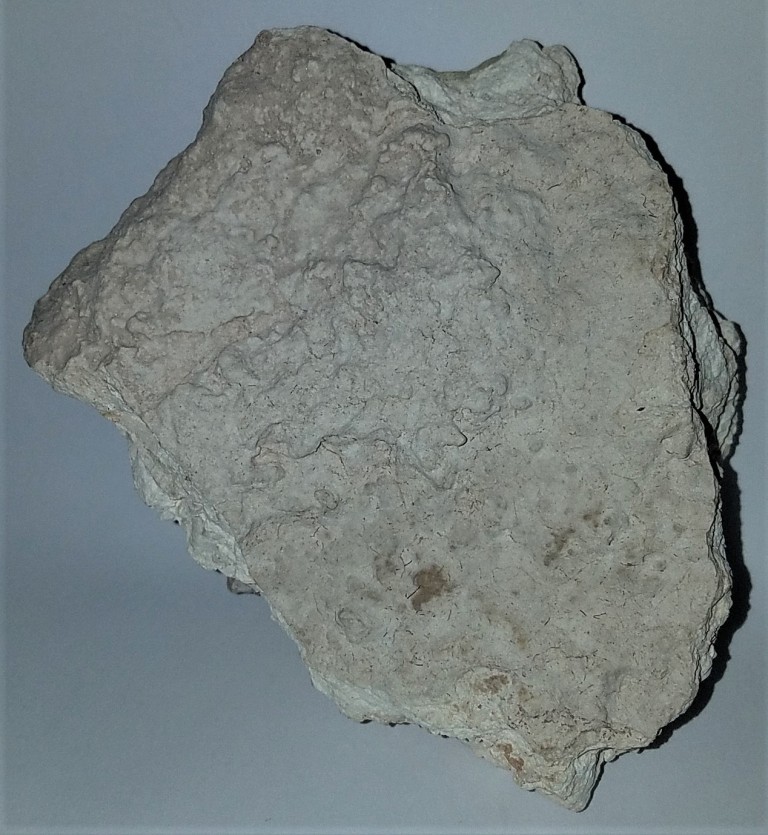

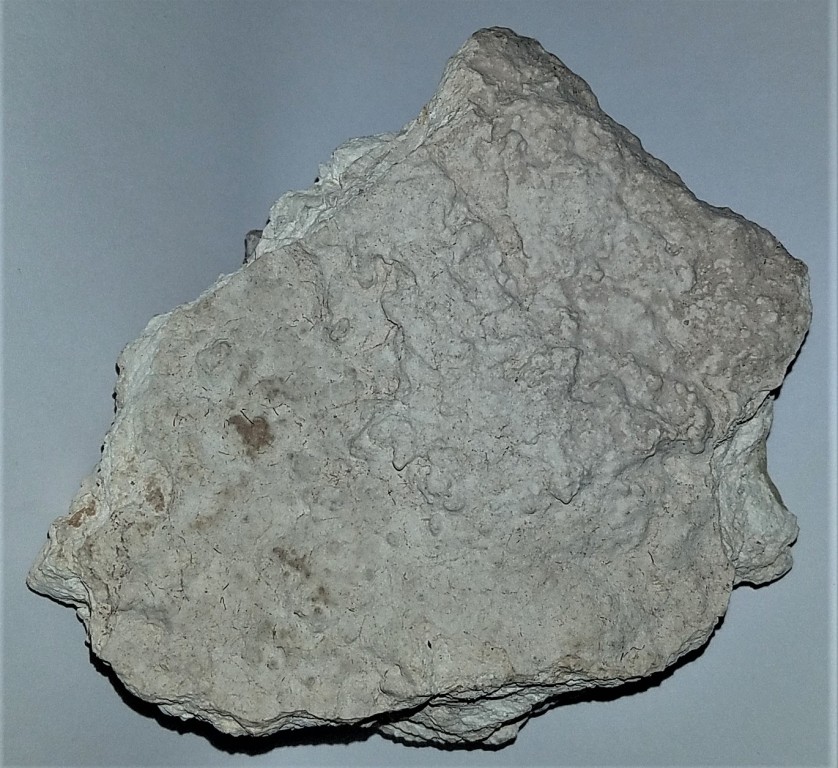

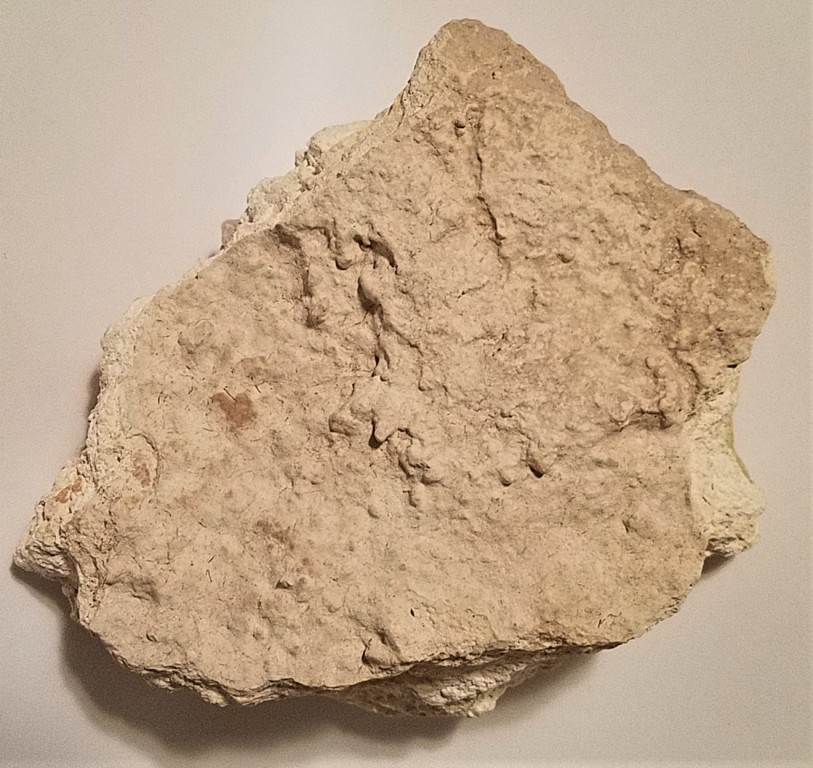

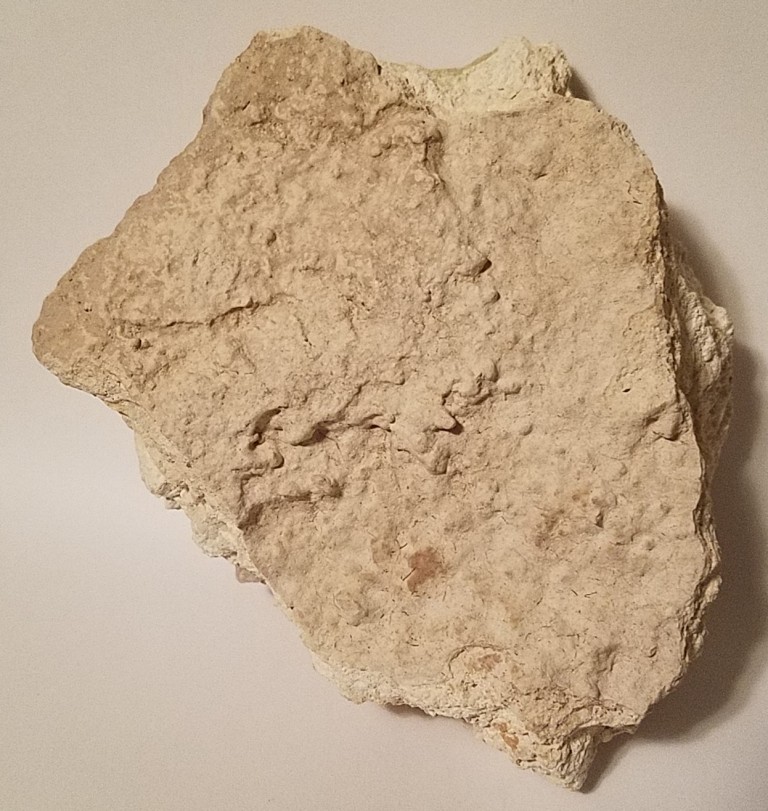

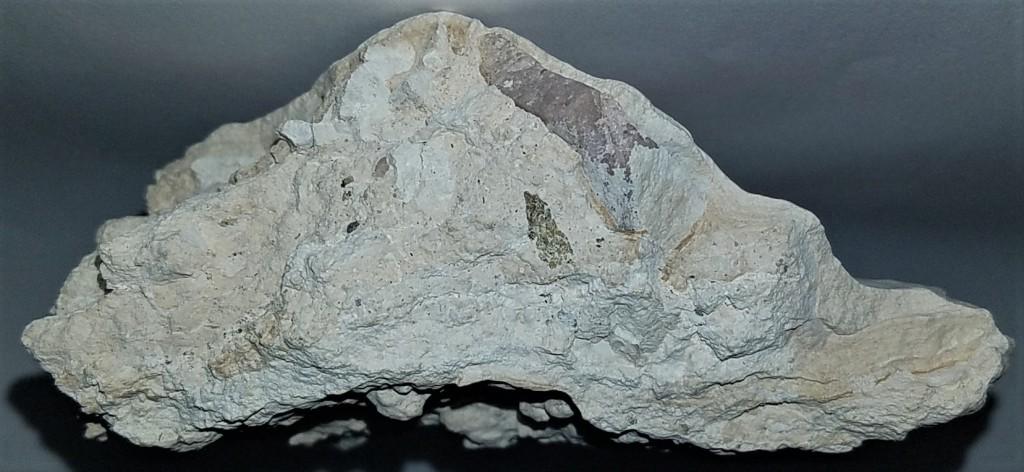

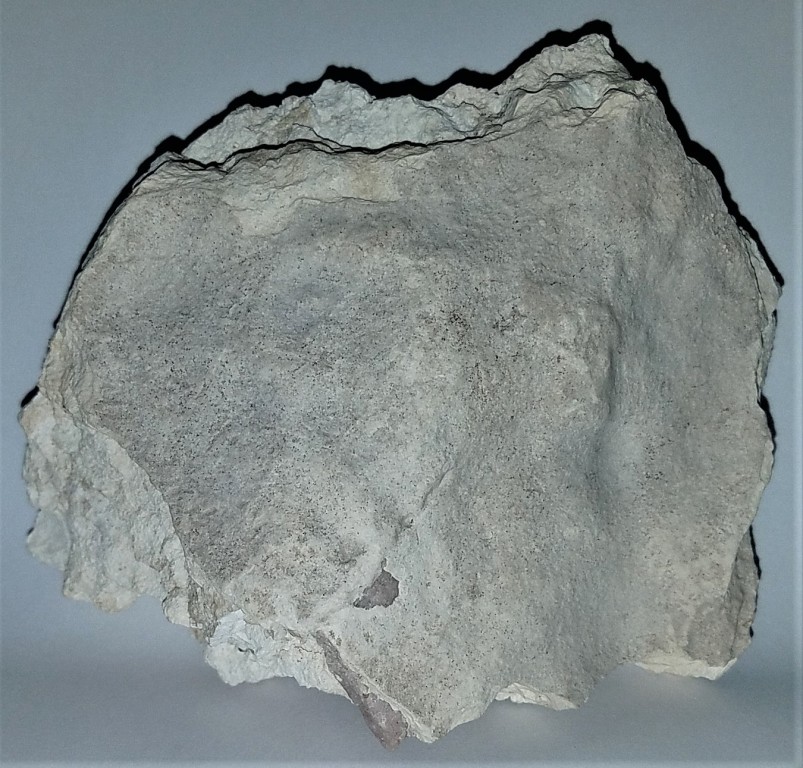

Caliche

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Photographed by Michael P. Klimetz

Pioche

Lincoln County

NEVADA

Caliche is a sedimentary rock which, in simplest terms, consists of clastic particles cemented by calcium carbonate. It occurs worldwide, generally in arid or semiarid regions, including the High Plains of the western USA, the Sonoran Desert, and the Mojave Desert. Caliche is also known as calcrete. Caliche is generally light-colored but can range from white to light pink to reddish-brown, depending on the minerals present. It generally occurs on or near the surface but can additionally be found in deeper subsoil deposits. A caliche layer can range from a few inches to several feet in thickness. Multiple layers can be present in a single location. A caliche layer in a soil profile is referred to as a K-horizon. Caliche forms where annual precipitation is less than 65 cm (26 in) per year and the mean annual temperature exceeds 5°C (41°F). High rainfall leaches excess calcium from the soil. while in very arid climates, rainfall is inadequate to leach calcium whatsoever and thin surface layers of calcite are formed. Plant roots play an important role in caliche formation, by releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide into the A-horizon of the soil. Carbon dioxide levels here can exceed 15 times normal atmospheric values. This allows calcium carbonate to dissolve as bicarbonate. Where rainfall is adequate but not excessive, the calcium bicarbonate is carried down into the B-horizon. Here there is less biological activity, the carbon dioxide level is much lower, and the bicarbonate reverts to insoluble carbonate. A mixture of calcium carbonate and clay particles accumulates, first forming grains, then small clumps, then a discernible layer, and finally, a thicker, solid bed. As the caliche layer forms, the layer gradually becomes deeper, and eventually moves into the parent material, which lies under the upper soil horizons. However, caliche also forms in other ways. It can form when water rises through capillary action. In an arid region, rainwater sinks into the ground very quickly. Later, as the surface dries out, the water below the surface rises, carrying up dissolved minerals from lower layers. These precipitate as water evaporates and carbon dioxide is lost. This water movement forms a caliche that is close to the surface. Caliche can also form on outcrops of porous rocks or in rock fissures where water is trapped and evaporates. In general, caliche deposition is a slow process, requiring several thousand years. Caliche can be thought of as a shallow layer of soil or sediment in which the particles have become cemented together by the precipitation of mineral matter in their interstitial spaces. The cement is usually calcium carbonate. However, cements of magnesium carbonate, gypsum, silica, iron oxide, and a combination of these materials are known. Caliche is a common feature of arid or semiarid areas throughout the world. In the United States, caliche is a familiar deposit in many parts of the Southwest, especially in Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas. There, caliche is associated with problems such as poor soil drainage, difficult soil conditions for plant growth, and excavation problems at construction sites. In some locations there are multiple ancient caliche layers in the subsurface. The term "caliche" originates from a Spanish word for porous materials that have been cemented by calcium carbonate. The name is used to refer to a piece of the material or the layer from which it was broken, or the cement itself that binds the materials together. Caliche is known by many other names, the more common of which are calcrete, hardpan, duricrust, and calcic soil. Typical caliche colors are white, gray, brown and reddish-brown. Well-developed caliche can have an appearance that resembles conglomerate, breccia, coquina, or sandstone if the cemented particles are of the proper type and size. Caliche can be a very hard, dense, heavy, and durable material if it is firmly bound by a cement that completely fills the interstitial voids between the soil or sediment particles. It can also be a weak and friable material if it is poorly cemented. In excavations and outcrops, a well-developed caliche usually stands out as a competent, well-cemented sediment or soil with loose friable material below. Sometimes it is overlain by uncemented surface material. Caliche has a diversity of origins.

The principal process of caliche formation, in sedimentological and geochemical terms, commences when calcium carbonate is leached from upper soil horizons by downward-percolating solutions. Dissolved calcium carbonate might also be delivered to the site in runoff and then percolate into the soil. The calcium carbonate then precipitates in a deeper soil horizon to form the caliche layer. At first the calcium carbonate precipitates as small grains or thin coatings on sediment grains or soil particles. As the grain coatings thicken, adjacent grains will be cemented together, and nodules consisting of multiple grains and their surrounding cement will form. As cementing continues, a continuous subsurface layer might form. At advanced stages, a solid caliche layer can develop. These can become so dense and impermeable that they can resist the downward percolation of water and erosion by wind or water. The caliche layer generally has a higher density at the top and decreases downward. Advanced caliche formation can produce a layer that is over one meter thick and have a lateral extent of hundreds of square kilometers or more. Some caliche forms by the upward movement of water through capillary action. As the water evaporates, dissolved materials precipitate, and, over time, can cement the soil or sediment. Caliche can also form beneath vegetation that extracts water from the ground and transpires it into the atmosphere. As large amounts of water are removed by the plants, mineral materials that the plants do not remove become concentrated in the subsurface waters. When the concentration becomes high enough, or evaporation occurs, precipitation begins and can form caliche over time.